Here at Bluearth, our goal isn’t just to increase levels of physical activity, but to improve movement and meaning through a lifespan. Knowing that motivation is the key ingredient to moving well over a lifetime, we understand and harness dimensions of motivation in everything we do.

We are guided by principles of Self-Determination Theory, which is a comprehensive framework outlining the motivators of choice behaviour and personal development. Part of this framework, which we take into consideration, is the continuum of motivation. This continuum is what we’ll be exploring in this blog, so read on to learn more.

About the motivation continuum

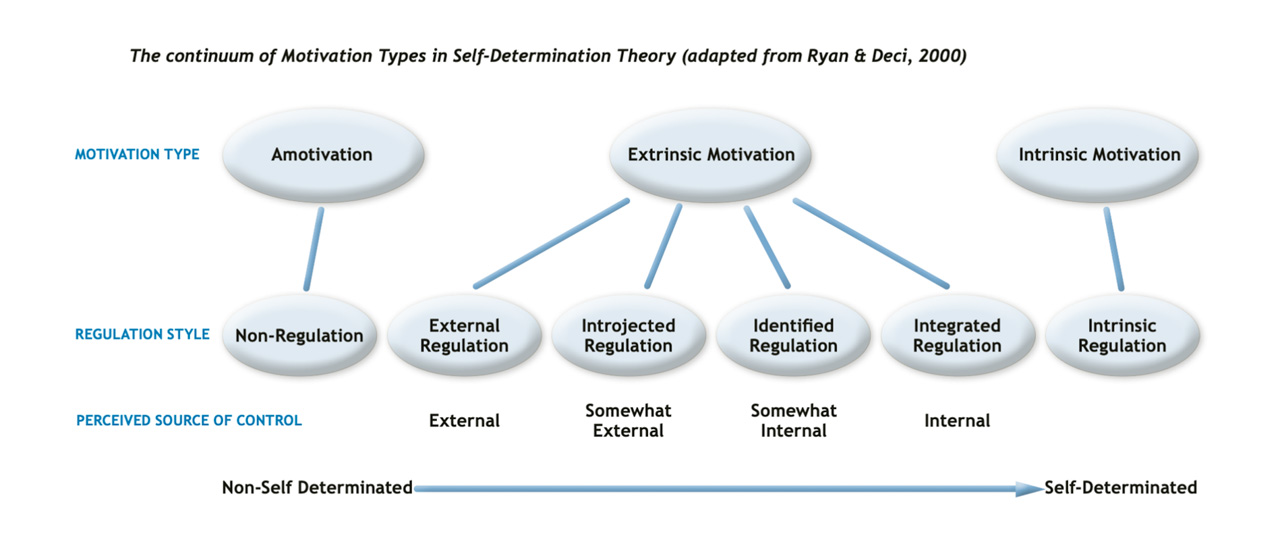

The Self-Determination Theory framework identifies six distinct types of motivation based primarily on the degree to which a person will consider themselves—as opposed to an external agent—the primary source of their motivation in any given situation. The more that one perceives the motivation to be their choice, the more they consider themselves in control and therefore the more likely they are to experience a sense of self-determination.

The motivation types lie along a continuum of increasing autonomy, ranging from amotivation (a total lack of motivation) to intrinsic motivation (the motivation to act in the interest of living the experience and being involved in the process), as shown in the diagram below.

It’s important to keep in mind that this is a continuum of self-determination, not a strict developmental progression. Amotivation, or even external regulation, aren’t necessarily starting points; for example, children often engage in activities purely from intrinsic motivation. Ultimately, the events and outcomes experienced by an individual will determine the maintenance or change of their motivation type.

A breakdown of the motivation continuum

Amotivation

Starting off the continuum is amotivation, which represents people who don’t attempt a behaviour at all, or if they’re in a situation that calls for a behaviour, they simply go through the motions without any personal intent.

People who are amotivated find no meaning or value in the activity, nor do they expect any particular rewards/punishments that would motivate their behaviour. This may come down to reasons such as ignorance, a feeling of being completely incompetent, or a lack of any control over outcomes in the area. In any case, the person has no reason to engage, and if they do, it’s only to passively go along because there is no stronger motivation.

Take note, amotivation does not describe motivation to avoid the behaviour either passively (e.g. passive resistance) or actively (e.g. misbehaviour).

External Regulation

Moving on, external regulation is most obviously and completely controlled by external forces.

External regulation is aligned with classic behaviourism and is driven by situational stimulation and reinforcement through rewards and punishments. For example, we’re acting from external regulation when we do a distasteful job for pay or slow down when we see a speed camera. These sorts of extrinsic reward/punishment contingencies are widespread throughout society, school, and physical activity (particularly sport).

Introjected Regulation

As we move along the continuum, the motivation type becomes more internalised. With introjected regulation, the person has replaced the objective, extrinsic reward/punishment contingencies with internal ones. This internal source may be a sense of ‘being good’, but more often it’s guilt or anxiety about not doing the right thing or doing the wrong thing (and being caught and punished).

The motivation therefore is not so much self-determined, but more an internalisation of external rules and the trained internal rewarding or punishing. An expectation also often exists that virtuous or dishonourable deeds will eventually result in extrinsic rewards or punishments, respectively.

Identified Regulation

This is where we begin to witness behaviour that’s motivated by personal choice.

With identified regulation, the individual has identified a behaviour as important and valuable for attaining some personally desired objective; as a result, they value an activity as a means to an important end and perceive it as worthwhile even if it’s not enjoyable for its own sake.

We see many examples of identified regulation in exercise and sport, where the desire for health or performance outcomes leads to a commitment to training that may be hard or unpleasant. Ultimately, people will choose to put in tremendous effort, on their own accord, if they want the expected benefits badly enough.

Integrated Regulation

As the motivation continuum diagram indicates, the level of self-determination an individual possess increases as we move to integrated regulation.

Instead of simply a means to an end, the choice to act becomes a congruence with how the person perceives themself and the values guiding all aspects of their lives. They now choose and engage in the behavior because it is who they are.

Since integrated regulation represents a level of development where personal values are completely synthesized into the self, the motivation can be clearly identified as internal or self-determined. For this reason, integrated regulation is often considered akin to (and sometimes labeled as) intrinsic motivation. However, the difference from true intrinsic motivation is that the behaviour is desired and appreciated because it’s in harmony with learned self-perceptions and values, not because it’s inherently enjoyable or satisfying.

Intrinsic Motivation

At the end of the motivation continuum is intrinsic motivation. This is the choice to engage in activity for the satisfaction and pleasure gained in the experience of doing it, beyond any other benefits. While there may be other extrinsic benefits of the behaviour, the doing of it is a sufficient enough reward.

This inherent tendency to seek out challenges, explore possibilities, and enjoy engagement in active living has been noted by psychologists as a sign of healthy development and the positive potentials in human nature. The key is that intrinsic motivation is self-perpetuating. The activities are pursued out of personal choice and the reinforcements for choosing the activity are present in the experience itself as much as any other personal gain.

This is crucial when it comes to lifestyle choice behaviours, as there may be few external incentives (e.g. enticements, social support, perks, payments), even disincentives (e.g. time, effort, lack of social support, inconvenience), and the health and wellbeing rewards/costs may not be immediately apparent, if ever.

Purpose, Experience, and Outcomes

Each motivation type is unique and creates different influences on the nature of engagement, learning, performance, and personal outcomes of the activity at hand. Specifically, the level along the continuum determines the purpose for acting, the cognitive/emotional experience of acting, and the types of rewards sought from the action. In turn, these experiences and outcomes will increase or decrease the likelihood of choosing the behaviour again in the future.